Asbestos waste is killing a remote First Nations community – and the WA government has known for decades

A powerful new film exposes how deadly asbestos is destroying lives and land on Banjima Country

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article contains images and names of deceased persons.

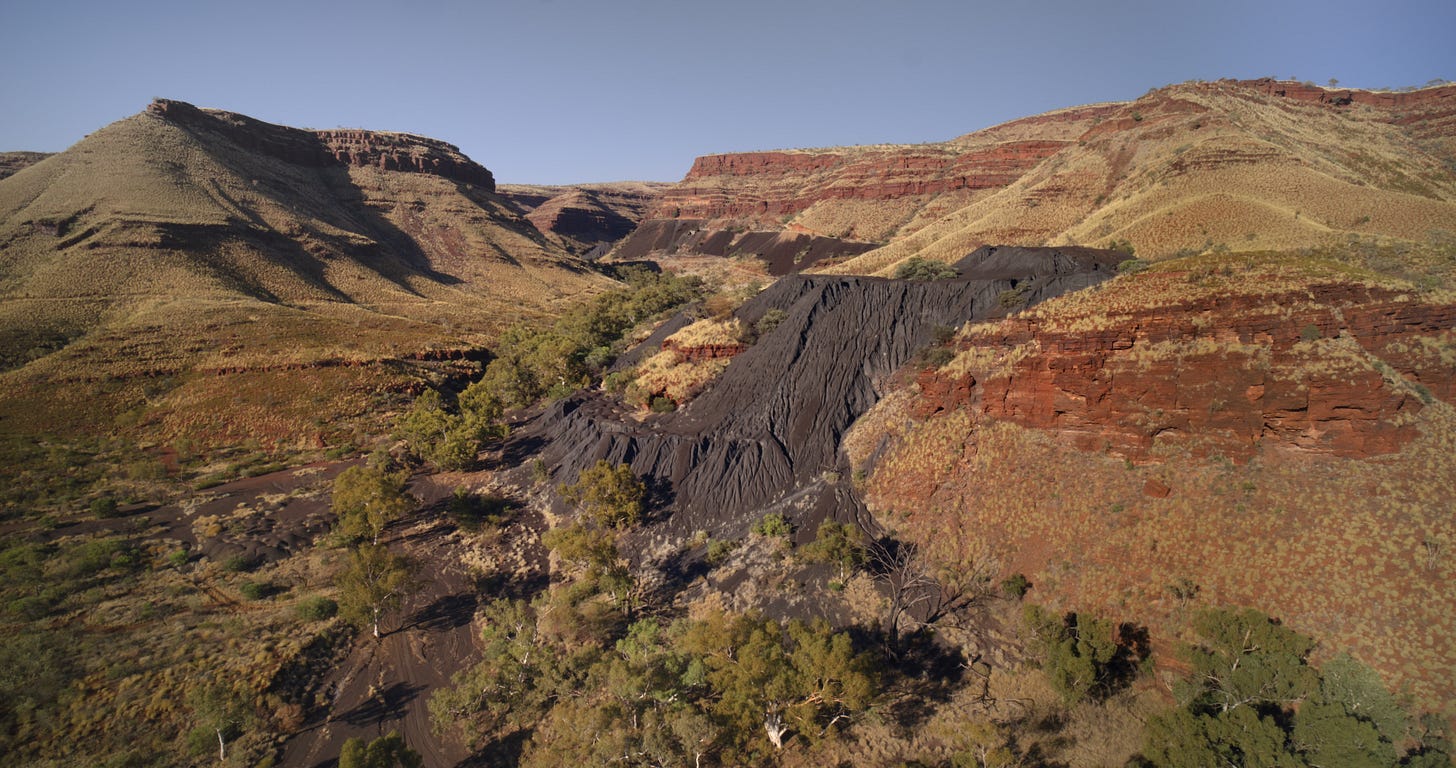

It’s the largest contamination zone in the southern hemisphere – eight times the size of Sydney Harbour. For two decades, the WA government has known that asbestos from now-defunct mines in the Pilbara was spreading, far and wide, killing members of an ancient First Nations community – the Banjima.

“For Banjima, it is now a part of our oral history about how our families lived on Wittenoom,” Johnnell Parker says, referring to the now-erased mining town that sat 1,420kms north of Perth.

Wittenoom was built in 1948 to serve asbestos mining that commenced in the 1930s. Mining operations – originally partly owned by Lang Hancock, the father of billionaire Gina Rinehart – continued until 1966, when they were closed for economic reasons. The town was erased in 2007, but the asbestos remained, contaminating the air, filling the lungs of a community that has dwelled on the land for millennia.

“Three million-plus tons of asbestos waste have been left on Banjima Country and it is spreading,” says Yaara Bou Melhem, director of Yurlu Country – a powerful new documentary that focuses on Wittenoom’s asbestos legacy on the Banjima.

Highest rate of deaths from mesothelioma

The lingering effects of Wittenoom have been devastating.

‘The Banjima people have the highest death rates from mesothelioma globally,” Bou Melhem tells Deepcut. Mesothelioma is an asbestos-related cancer.

Her film tracks the story of Banjima elder Maitland Parker.

“He wasn’t someone who mined in the Wittenoom asbestos mines. He lived in the Karajini National Park,” she says. Karijini is considered one of Western Australia’s most spectacular national parks.

“He was a park ranger there and lived there for 40 years. But his service as a ranger went through Wittenoom and the tailings area.”

Parker co-created the film with Bou Melhem, but did not live to see its release. Parker passed away from mesothelioma during production – a disease that rippled through his body after years of travelling through his native land.

“They may have buried the buildings, but that contamination is still very much part of our lives,” Johnnell, Maitland’s niece and board director of the Banjima Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, told a Q&A on November 10, hosted by Documentary Australia.

“We’ve lost elders, and not just Banjima Elders – this has touched all community groups.”

Killing the connection to Country

Senator Lidia Thorpe says the mine is not only killing the Banjima people, “it is also killing their ability to look after Country, the ability for Elders to pass on knowledge to younger generations. It’s killing Country and culture as well”.

Johnnell knows that all too well. “Our elders now have this disease because they’ve still maintained those connections to Country, going out on Country,” she says.

“Us as Banjima have never moved off our lands. Traditional Owners very rarely leave their homelands, and then when Country is sick, we are the ones that can ask that question ... who fixes it? How do we protect our lands?”

The film conveys the deep, intimate bond the Banjima have to their Country – a bond rooted in tens of thousands of years of history, passed down through generations. It’s a way of life now under threat by untamed asbestos.

“It wasn’t that Banjima people were forced off their lands. It’s that they can’t go there safely. We get told and it’s in a lot of the reports that we’ve seen that Banjima people still go to the Wittenoom area to practice culture, lore and ceremonies,” Bou Melhem says.

The government knew and did nothing

In 1978, the WA government closed Wittenoom due to the health hazard posed by asbestos waste. In 1985, a government-commissioned report estimated the clean-up would cost at least $22.1m.

But no action was taken.

In 1992, a WA parliamentary inquiry recommended the tailings at the mine site be cleaned up “over a five-to-ten year period”. The report’s recommendations were rejected by the WA cabinet at the time.

In 2006, a state government report first drew attention to the impact on the Banjima. It found up to 200 First Nations people continued to use the gorges for ceremonies – activities it considered high-to-extreme risk.

In 2015, another government-commissioned report estimated remediation at the site would cost $150m, warning the asbestos waste could spread for “hundreds of years”. Again, no action was taken.

“This is another stark and tragic example of how governments don’t care about our people. It’s just another remote community, just some Blakfellas,” Thorpe tells Deepcut.

‘A silent genocide’

“This condoning of the killing of our people, of standing by to see our people slowly die without taking any action, this is part of the genocide that continues in this country to this very day,” Thorpe says.

Deepcut asked the WA Labor government why it had failed to clean up the asbestos, despite knowing its deadly effects on the Banjima. We received no reply.

We also sent numerous questions to the office of federal Indigenous affairs minister, Malarndirri McCarthy – a spokesperson redirected the matter with the below response:

“This sits with the Asbestos and Silica Safety and Eradication Agency (ASSEA) as well as the WA government to respond,” they said.

For Senator Thorpe, the most prominent First Nations voice in the federal parliament, the WA government’s inaction “is a symptom of the colonial industrial complex that has successfully engaged in a silent genocide on our people since the boats arrived”.

Bou Melhem says the government’s failure to act “speaks to this very colonial mentality of this being out of sight, out of mind for most Australians and almost, whether it’s deliberate or not, a process of erasure.”

Potential lawsuit

The Banjima, however, are not giving up.

“Despite the impacts on Country, our elders have built us to be strong, resilient people to take on the next phase of the fight,” Johnnell says.

The community has engaged high-profile lawyer Peter Gordon to take on the WA government.

Gordon has been down this road before, helping run cases on behalf of miners and residents impacted by asbestos in Wittenoom in the 1980s and 1990s.

“They’ve circled back in what is unfinished business for them to resolve this issue of contamination,” Bou Melhem says.

The struggle is not merely about compensation for the health consequences suffered by the Banjima – it’s also about healing the land. For the Banjima, land and community are one.

“The land is our identity, we are a part of it just as much as it is a part of us,” Johnnell says.

“Even when the land becomes of no commercial use to anyone, it will always mean something to us as First Nations people.”

Yurlu Country is currently screening at cinemas across Australia, the details of which can be found here.

Donations to the Wittenoom Cleanup Campaign can be made here.

Both WA and federal governments are accountable for their inaction. The 2015 report was clear, the contamination is spreading and people are dying from it. We must keep up the pressure on WA gov and the Feds to act immediately.