Australia's recognition of Palestine is a fantasy divorced from history

The two-state solution is not a step toward justice – it's a cover for permanent occupation

By recognising a Palestinian state, the Albanese government has aligned itself with a two-state vision that no longer reflects the facts on the ground – nor does it offer Palestinians any real hope for justice, sovereignty, or survival.

Critics have already pointed out the obvious – that such a declaration holds little value without tangible action to stop Israel's genocide in Gaza.

As the Australia Palestine Advocacy Network said in its statement yesterday, "Recognition is completely meaningless while Australia continues to arm, trade with, diplomatically protect and encourage other states to normalise relations with the very state perpetrating these atrocities, and with Israeli leaders wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes".

The prime minister said yesterday that he was seizing upon "a moment of opportunity". Except recognising a state that is in no condition to be formed will not halt Israel's actions in Gaza, nor will it prevent a further loss in Palestinian life – a fact made clear by Benjamin Netanyahu, who said, "It's not going to change our position".

Beyond having little impact on the war today, the quest for a two-state solution reveals a lack of imagination to craft a political settlement that meaningfully reflects the current political and territorial landscape.

Western governments are stuck in the 1990s

Albanese touted the two-state solution as "humanity’s best hope to break the cycle of violence in the Middle East and to bring an end to the conflict, suffering and starvation in Gaza". Nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, such a statement demonstrates the Australian government's profound lack of understanding of the context in Palestine and the steps required to address the entrenched structural conditions that sustain the conflict.

The two-state solution was all the rage in the 1990s, when then-Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat famously signed the Oslo Accords with the then-Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, under the auspices of US president Bill Clinton.

Following US leadership, western governments adopted the 'two-state solution' mantra and have repeated it ad nauseum since the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993 – even as circumstances on the ground dramatically shifted in the subsequent three decades.

But the original two-state proposal was less about the establishment of two sovereign states, and more about legitimising Israeli occupation.

Under the Oslo Accords, Israel would recognise Palestinian sovereignty over the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in exchange for Palestinian recognition of Israel in the remaining territories of historical Palestine. The disadvantages for the Palestinians, however, were clear from the outset.

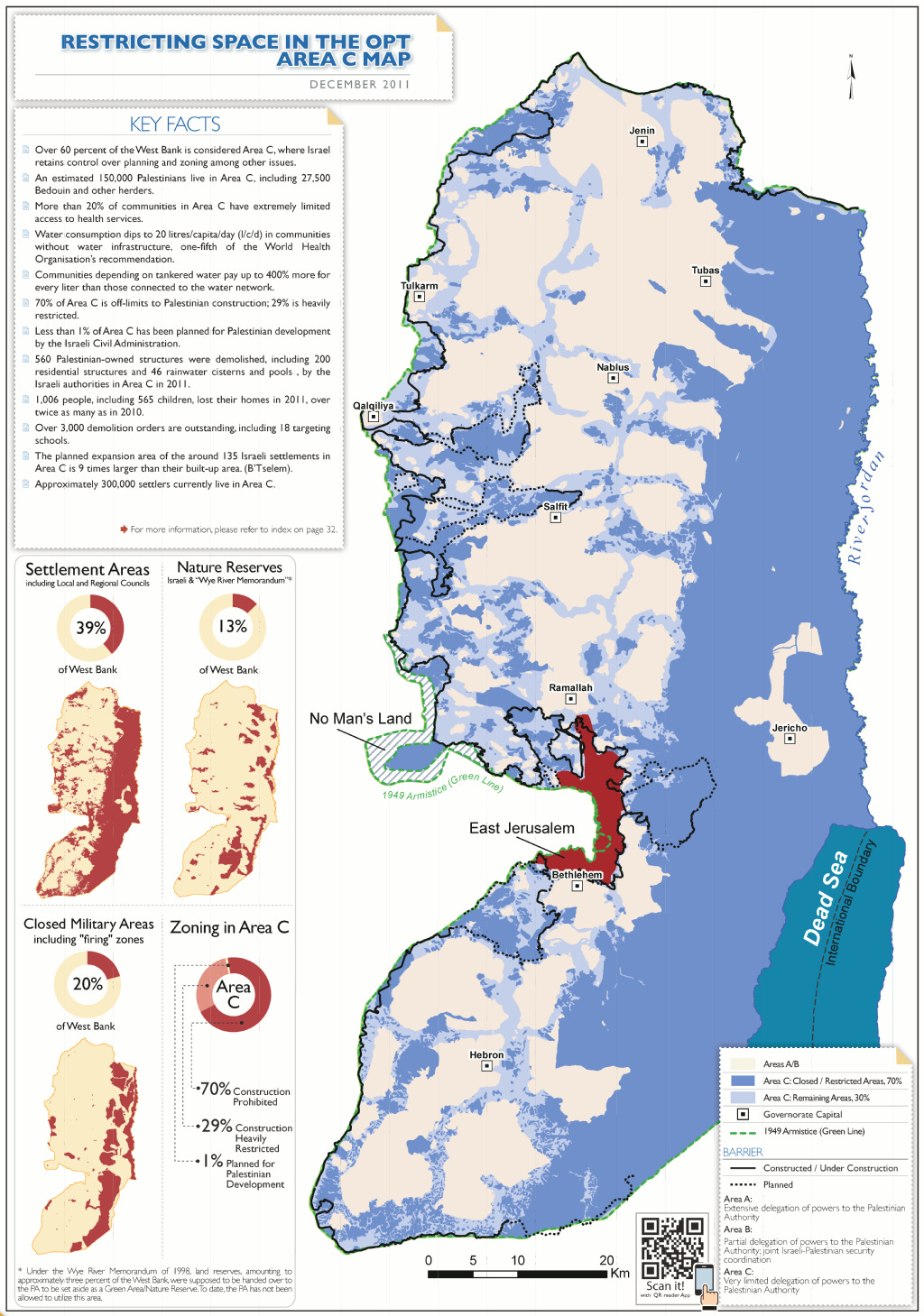

The Palestinians would not have full control of the West Bank – they would control only 18% of the land under a designation known as 'Area A'. Israel would retain control of 60% of the land under 'Area C'. This essentially meant the Palestinians would have a Swiss-cheese map of a state – cities, towns and villages separated by Israeli-controlled zones. Even with a so-called 'independent' state, Palestinians would still have to travel through Israeli checkpoints to go from one city or town to another.

Israel would also control much of the West Bank's vital water resources, airspace and borders. Under a new deal proposed by Clinton and then-Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak in 2000, the Israeli military would also reserve the right to enter Palestinian-controlled areas if they perceived a threat (note: this is exactly the same policy Israel is attempting to enact over south Lebanon and southern Syria today).

This flawed notion of a sovereign state is exactly what Albanese had in mind at his press conference yesterday, when he called for the "demilitarisation of any future Palestinian state" and "the potential role for international forces in security".

Two states are not realistic, for either side

Even with a legitimised occupation dressed up as "humanity's best hope" for peace, the circumstances in 2025 have rendered obsolete a roadmap signed in 1993.

In 1993, the Israeli settler population in the West Bank and East Jerusalem was 250,000. By 2023, it had grown to 700,000. While western governments have been issuing press statements on a 'two-state solution' for three decades, every Israeli government since the Oslo Accords has expanded settlements to prevent a Palestinian state. And they've succeeded.

Given how extremely Israeli society and politics have drifted – to the point where 79% of Israelis today shrug their shoulders at the thought of starving Palestinians – it is inconceivable that any Israeli government will emerge with a policy to evict settlers from the West Bank. Any that tried would undoubtedly spark a civil war.

But even if such a government were to emerge, why should Palestinians accept a version of sovereignty that entrenches their subjugation – as laid out in the Oslo Accords and echoed in Albanese's remarks?

They didn't in 2000. Arafat signed the first set of accords in 1993, but refused to sign the new deal proposed by Clinton and Barak. Arafat knew it was tantamount to what Edward Said described as "an instrument of Palestinian surrender". Not only would Israel maintain its occupation in all but name, there would be no return for the millions of Palestinian refugees expelled from their lands in 1948 and still living in squalid camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.

A shift in historical framing is needed

Albanese was right when he said that "history casts a long shadow". But he also noted that "Australia was the first member of the United Nations to vote for back in 1947 [sic], when we proudly supported the creation of the modern State of Israel as a state for the Jewish people ...".

This statement alone exposes the flaw in Australia's policy approach to Palestine. Nearly eight decades later, the Australian government still has not acknowledged the grave crime inflicted upon the Palestinian people, and its role in it.

Albanese ignores history when he refuses to recognise that the Palestinians were the victims of an unwanted, violent settler colonial project. Australia's support for this colonisation helped enable Israel's ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians from their native lands in 1948. It's a role Australia is still playing today.

What Albanese has demonstrated, however, is Australia's remarkable consistency – that a prime minister would express pride in the colonisation of a native people's land, while leading a federation that came to be through the same means.

A new solution grounded in reality and history

Acknowledging Israel's violent colonial origins – and present – does not erase Israel's existence today. Nor would Australia be erased should it acknowledge, truly, its own violent colonial origins.

What it does, however, is provide an avenue for a realistic, just path forward. There cannot be sustainable peace without the restoration of justice to the native Palestinian population. Being holed in surveilled enclaves called the 'state of Palestine' is not justice, and would not engender a sustainable peace – as we can see with the atrocities being committed in Gaza today.

Allowing the native population to return to their historical lands across Palestine, where they enjoy full equality with Jewish citizens, is the only feasible path to a just resolution of this tragic story. It's about time western governments caught up to that reality.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in West Asia:

Lebanon:

Lebanon dominated West Asia news last week after the Lebanese government endorsed a US plan to disarm Hezbollah by the end of the year. Shiite ministers withdrew from the cabinet meeting before the vote, which sparked protests by pro-Hezbollah supporters throughout the country. Hezbollah has vowed not to surrender its weapons and insisted that Israel comply with the ceasefire terms agreed to in November 2024. Israel has violated the ceasefire more than 3,000 times and killed over 230 Lebanese, and continues to occupy five strategic locations in south Lebanon.

My take: The Lebanese population is exhausted. It was on the faces of everyone I spoke to when I last visited in March 2024. And that was before the war escalated over the northern summer. The people have suffered crisis upon crisis. Most Lebanese still haven't recovered from losing their life savings in the 2019 financial collapse. Disarming Hezbollah has significant support from within the country who are desperate for an end to mayhem. And that is entirely understandable.

Unfortunately, however, that desperation is masking the existential threat facing the country. Israel wants Lebanon disarmed and incapable of defending itself. Israel wants to dominate Lebanon, and in particular, south Lebanon, which its most extreme actors still seek to colonise. Regardless of the misgivings many Lebanese have about Hezbollah, the group has positioned itself as central to Lebanon's national defense. It is stronger than the Lebanese army. Removing Hezbollah's arms without a Lebanese-led defense strategy that would replace Hezbollah vis-a-vis the Israeli threat is tantamount to national suicide. It isn't a Lebanese-led initiative that is seeking to disarm Hezbollah today, it's US-led, on behalf of Israel, to dismantle the one force standing in Israel's way in Lebanon.

Lebanese deserve an end to their seemingly endless nightmare. But many are wrong to assume that the nightmare comes from within. Israel makes its own calculations, and none of their calculations include Lebanese prosperity.

Egypt:

Egypt's pro-US president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, chastised Israel last week for "systematic genocide to eradicate the Palestinian cause". And then his government signed a US$35bn deal to import gas from Israel.

Syria:

Roughly 10,000 people have been killed since the new extremist regime under Ahmad al-Sharaa took power in Syria in November last year, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. Sharaa, who was formerly the al-Qaeda leader in Syria, has aligned himself to the US-Gulf Arab axis in the region, while carrying out systematic attacks on the nation's various minorities.