Iran protests show US sanctions working as intended

Sanctions have cost Iran's economy $1 trillion and are fuelling economic grievances

This piece is part of our series, West Asia Focus, where we take a closer look at the region’s geopolitics, grounded in expertise and indigenous perspectives.

There have been enough protests in Iran in recent years to acknowledge that genuine, public discontent exists.

Yes, it’s likely that Mossad cells are active in Iran, given they revealed their presence in last year’s 12-Day War. It’s probable too that US intelligence is also operating in the country, as suggested by the 50,000 Starlink terminals said to have been helping users bypass an internet shutdown.

But to dismiss the protests outright is to simplify the challenges Iran faces, and deny the hardship of millions of Iranians struggling to make ends meet. What these protests reveal is the effectiveness of US sanctions and the underlying economic pain they have caused over the years.

If the US, supported by Israel, were intending to create unrest by making Iranian lives miserable, the protests show it’s working, to an extent.

Sanctions put Iran on back foot

The protests began as a sincere outburst of economic frustration – a fact acknowledged by Iran’s President Masoud Pezeshkian, who said in late December that protesters had “legitimate demands”. The spark was a collapse in the nation’s currency at a time of ballooning inflation.

Even as Pezeshkian expressed a determination to “eradicate corruption, smuggling, and bribery”, there is little denying that the sanctions have been the primary source of Iran’s economic misery.

Iran has been under US sanctions since a revolution toppled the US-backed autocrat, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in 1979. Those sanctions intensified under the Obama administration in 2011 with the aim of crippling Iran’s oil trade, and have largely remained in place ever since.

According to one study, the sanctions since 2011 are estimated to have cost Iran at least US$1.2 trillion (A$1.78 trillion) and 23% of its economic capacity. A World Bank report noted “the economic cost of ongoing sanctions” as a major drag on growth.

The report also makes clear the significant economic risks of another direct war – a potential 7% contraction in Iran’s GDP. It’s a point no doubt shaping Iran’s aversion to a renewed war with Israel and the US.

Iran denied a $1 trillion economy

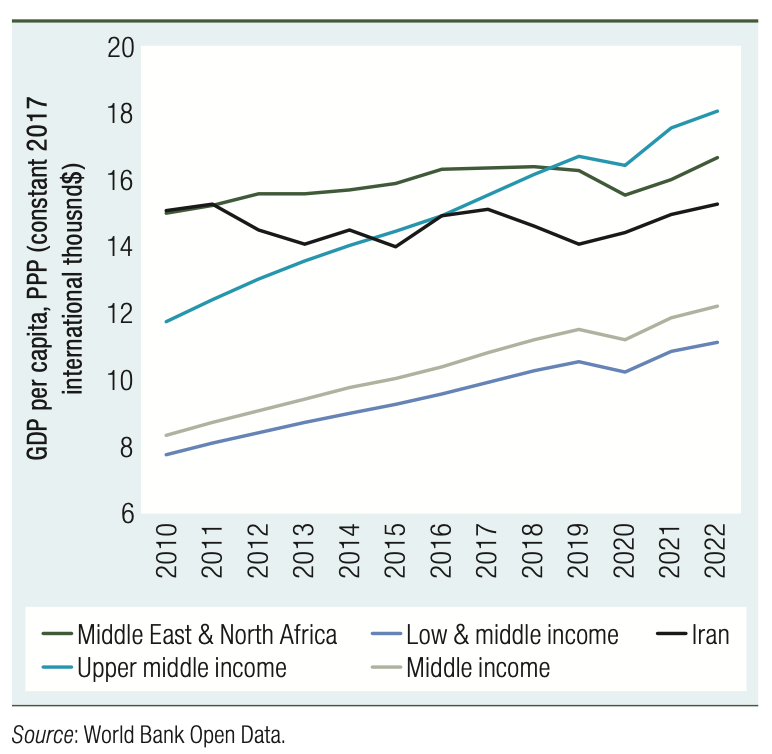

Iran has the largest gas reserves and fourth largest oil reserves in the world. Yet, it has been in the midst of sanctions-induced economic stagnation since 2011. The below World Bank chart shows Iran’s GDP per capita – once among the highest in the region – barely growing in real terms, only to be eclipsed by other upper middle income countries.

Living standards have, predictably, declined, but an alternative path was briefly unveiled in 2015 when Barack Obama signed a nuclear deal with Iran.

With promised sanctions relief, Iran, according to a McKinsey report at the time, had “the potential to add US$1 trillion to GDP and create nine million jobs by 2035”.

McKinsey identified Iran’s economic potential, in particular its diversified economy, domestic production base, large consumer market and high number of science graduates as strengths waiting to be realised.

But one obstacle stood firm against the 2015 deal: Benjamin Netanyahu. The Israeli prime minister’s vehement opposition, championed by the pro-Israel lobby in DC, saw the deal scrapped after the ascension of Donald Trump in 2016.

Israel understood, as McKinsey illustrated, that an Iran free of sanctions would become a West Asian economic powerhouse, denting its own ambitions at regional supremacy.

Iran’s strategy of force and compromise

While it’s difficult to ascertain the exact scale of this month’s protests, Iran’s rulers have also shown an ability to see off bursts of domestic unrest with a combination of force and compromise.

This is what occurred in 2022 when, in response to the killing of Mahsa Amini over a compulsory headscarf violation and the widespread protests it provoked, Iran’s leadership reportedly scaled back its enforcement of the hijab.

The response to the 2026 protests appears to be on par with Iran’s track record of protest crackdowns – Human Rights Watch reports growing evidence of “mass killings of protesters” and Ayatollah Khamenei himself admits thousands have been killed. Nevertheless, it would be a misreading to assume Iran’s leadership governs by force alone.

Iran’s leaders are acutely aware of the country’s economic pressures and have tried to massage the pain through monthly direct cash transfers. The World Bank report notes that the cash transfers as well as other social programs have “played a significant role in poverty reduction”. Between 2021 and 2023, “6.1 million Iranians were lifted above the poverty line”.

But these efforts have only softened the pain of sanctions. The stagnant economy has been unable to create a sufficient amount of jobs to absorb a high volume of educated workers. Iran’s overall labour participation rate is, according to the World Bank report, only 41.3% (Australia’s by comparison is 66.8%) – and dives to an abysmal 14.2% for women. Youth, university graduates and women are those “experiencing significantly higher unemployment rates”. No wonder they’re angry.

A well-understood intention of sanctions is to incite popular unrest through economic grievances. It’s an outcome Iran’s leaders seem to expect, and have experienced over the years. Far from being on the verge of crumbling, they appear to have a strategy in hand to deal with the outbursts of unrest – a blend of the carrot and the stick.

Ultimately, it’s a question of time, and whether Iran’s leaders have enough carrots to outlast US sanctions, and outlive broader US and Israeli efforts to undermine their rule and see Iran break.

If you have a story tip, drop an email to tips@deepcutnews.com or send an anonymous Signal to @deepcut.25.