Labor’s 5% deposit scheme will only make the banks richer – and that’s the point

The government’s new housing policy will see banks pocket billions in extra interest and saddle a generation with more debt

Labor’s latest 5% house deposit scheme housing policy – expanding the Liberals’ Home Guarantee Scheme – is a policy for bank profit, not first home buyers. It will drive up house prices, push first home buyers into more debt and deny thousands of low-income renters the chance to buy a home.

The Home Guarantee Scheme allows first home buyers to get a mortgage with just a 5% deposit, without having to pay for mortgage lenders insurance.

The policy creates a new state-backed incentive for first home buyers to take out larger loans. According to modelling from Lateral Economics, 146,446 first home buyers – people who would otherwise have waited to save a larger deposit or relied on their parents for a loan – will instead use the Home Guarantee Scheme and take out 95% bank loans. The current median dwelling price in Australia is $857,280, so assuming a standard mortgage rate of 5.74% and a 5% deposit (rather than a 20% deposit), a first home buyer will pay an extra $141,268 in interest.

In total, first home buyers will pay banks an extra $24 billion in interest off the back of the first five years of the policy alone. As the big four banks control 68.6% of the first home buyer mortgage market, they will collect an extra $16.4 billion in interest thanks to this new government policy.

And it will also make affordability worse. The same modelling suggests the scheme could increase house prices by 10% in the first year, by encouraging first home buyers to pay more than they otherwise would have by taking out larger loans, and redirecting the cost of lenders mortgage insurance towards a higher house price. As a result, 9,125 renters will actually miss out on buying a home due to house price increases that will be triggered by the policy.

It should not come as a surprise that Labor is spending public money to intensify the financialisation of housing – a system designed to enrich banks. After all, Labor helped create this profit-driven model in the first place.

A system for bank profit

From the 1990s onwards, housing has been a key element in the accumulation of capital in Australia. This was caused by three key changes:

Labor’s massive deregulation of the Australia financial and banking system in the 1980s and 1990s, allowing banks to lend more money to property investors

Labor’s decision to cut federal funding for public housing in 1995

John Howard’s Liberals introducing the capital gains tax discount for property investors in 1999.

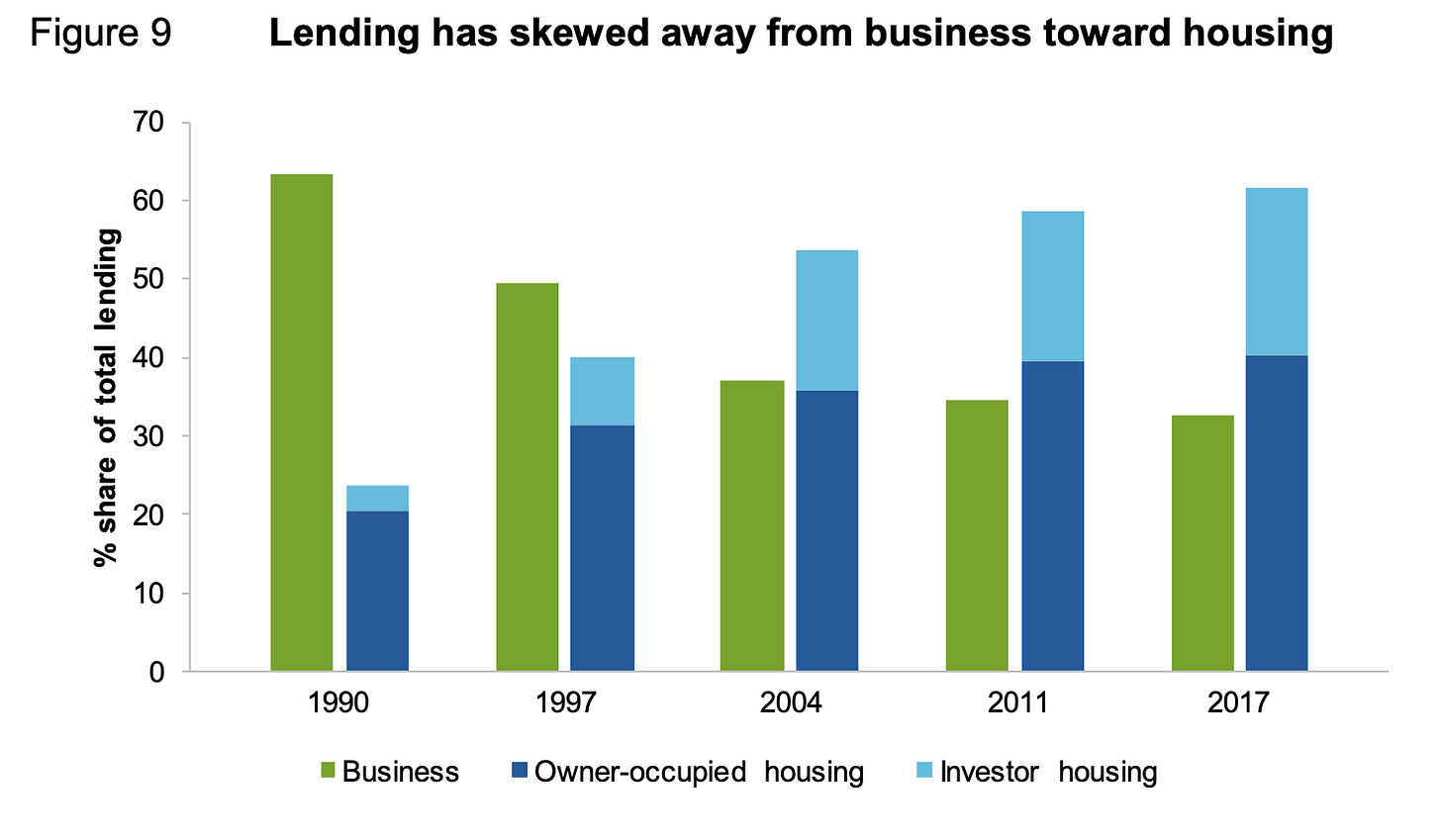

The best way to understand this fundamental transformation is through the banks and where they lend money. In 1990, over 60% of all bank lending went to businesses and just over 20% to housing, of which investor housing was a small fraction. By 1997, the total proportion of bank lending for housing loans doubled to over 40%, driven by an explosion in lending to investors, while loans to businesses dropped below 50%.

Today, 62% of all bank lending in Australia goes to housing and just 30% to business. That is the highest rate of any banking sector in the world, helping to make Australian banks the most profitable in the world. The consequence is that housing has become an incredibly lucrative financial asset, where the ultimate goal of the system becomes profit rather than providing affordable, well-designed homes as a right. This economic shift was fuelled by encouraging households to take on massive mortgage debts, to offset stagnant wages. As a result, Australia has the second-highest rates of household debt in the world.

In fact, last year alone the big four banks earned $44 billion in profit. That’s $1,619 each for all 27.2 million Australians. All up, Australians owe the big four banks $1.8 trillion in mortgage debt (that’s right, TRILLION). These same banks are the biggest and most profitable corporations in Australia, and Labor’s housing policy will make them even more profitable, at first home buyers’ expense.

The big four banks themselves are all owned by the same six multinational asset managers: BlackRock, Vanguard, HSBC, JP Morgan, StateStreet and CitiGroup, controlling on average 69% of the shares of each of the four banks. Which means Labor and the Liberals have created a housing system that forces millions of Australians to choose between crippling mortgage debt or insecure, expensive renting – just to line the pockets of mostly US-owned multinationals.

Tackling the housing crisis isn’t complicated

Ultimately, if we want a housing system that prioritises people, not profit, then we need to end the treatment of housing as a lucrative financial asset. To achieve that, we could:

Scrap the federal tax handouts for property investors, negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, and re-regulate the financial system to make it harder for banks to lend to property investors – in turn significantly reducing investor demand for housing

Coordinate national caps on rents, not just to protect renters, but to further reduce investor demand for housing. Investors rarely build new homes. They mostly buy existing homes that otherwise could have been purchased by a renter. So the more you reduce investor demand, the fewer renters there are in the rental market

Finally, start building public housing at scale. In Vienna, 60% of all housing is some form of rent-controlled social housing. Almost anyone in Vienna, regardless of their income, can access this housing, which means you get incredible social diversity and a financially viable housing system. But what you also get is beautifully designed, well-built medium density apartments, and a city with proper investment in public transport and public parks. Australia’s poorly designed and built apartments and urban sprawl ultimately come from a housing system designed for profit.

If you think something like the system in Vienna is not technically possible in Australia, it’s worth remembering that at the height of the Commonwealth State Housing Agreement in 1971, Australia was building 136 public homes for every 100,000 people in Australia. Today, that rate under the current Labor government is just 9.8 homes.

In 1995, had Labor not cut federal public housing funding and governments had instead built public housing at the same rate as we did in the 1970s, today we would have an extra 900,950 public homes. That would have increased Australia’s public housing stock by over 200%, eliminating the entire social housing waitlist.

Indeed, before Labor’s cuts in the 1990s, the federal government once included a standalone Department of Housing that employed thousands of architects, town planners, and builders.

Ultimately the question is social and political power

Labor and the Liberals will never fix the housing crisis, because both parties exist today to protect and expand a capitalist system that puts corporate profit over public needs. And a key pillar of Australian capitalism is housing. Both ultimately function as the political wing of a set of industries – banking, property developers, construction and real estate – that profit enormously from this system.

Historically and globally, the sort of changes Australia needs have come from mass political and social movements based on the power of a conscious, organised working class – not simply online articles or Instagram and TikTok videos. The added challenge in Australia is that the leadership of many established trade unions are captured by those integrated into the Labor Party that itself is creature of the capitalist state.

That doesn’t mean all hope is lost. But it does mean we need to start building a movement capable of challenging the power of Labor, the Liberals, the capitalist state and the big corporations who profit off this system on the backs of our labour, and our taxes.

Hell yes