PM's phone number leaked by foreign website – and Australian law can't stop it

Government urged to strengthen privacy laws and get tougher on companies after data of high-profile Australians published online

The prime minister’s phone number can be published online by a foreign-based website, and there is very little Australia can do about it under existing laws, according to experts.

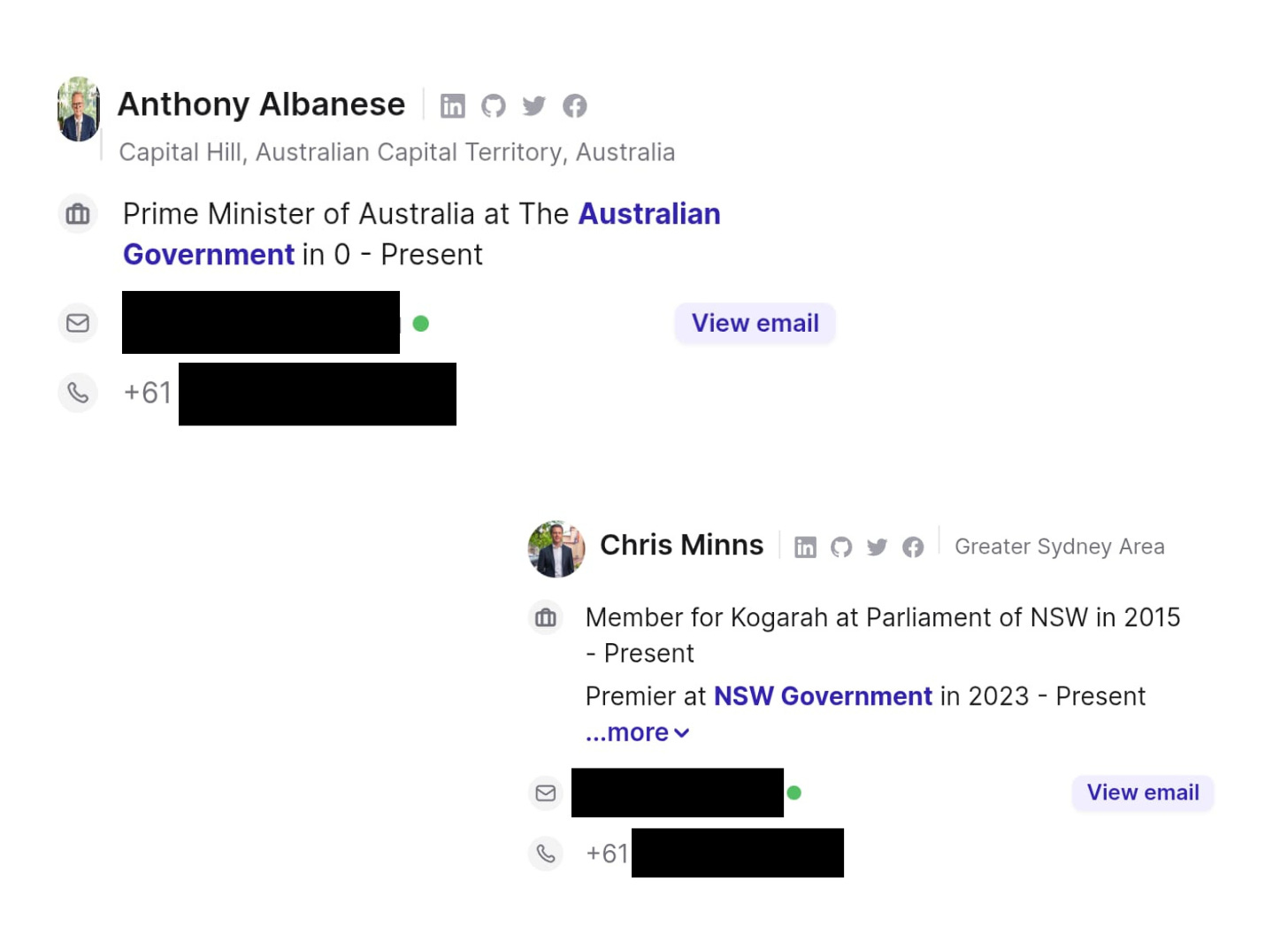

Privacy breaches are again in the spotlight after Ette Media revealed yesterday that a third-party website published the phone numbers of Anthony Albanese, opposition leader Sussan Ley, NSW Premier Chris Minns and a slew of other high-profile figures.

The website, belonging to a US-based data intelligence company and seen by Deepcut, allows for a number of free searches of its database of 800 million profiles, with 100 million phone numbers.

Its profiles include leading Australian politicians and public figures. It’s unclear how many Australians are listed on the company’s website.

“It’s unlikely that Australian laws could be used against [the company] directly as it’s not an Australian company,” Tom Sulston, head of policy at Digital Rights Watch, told Deepcut. “If it had more substantial business going on in Australia, it would likely fall under the Privacy Act and there would be useful laws that could get individuals’ data out of the system.”

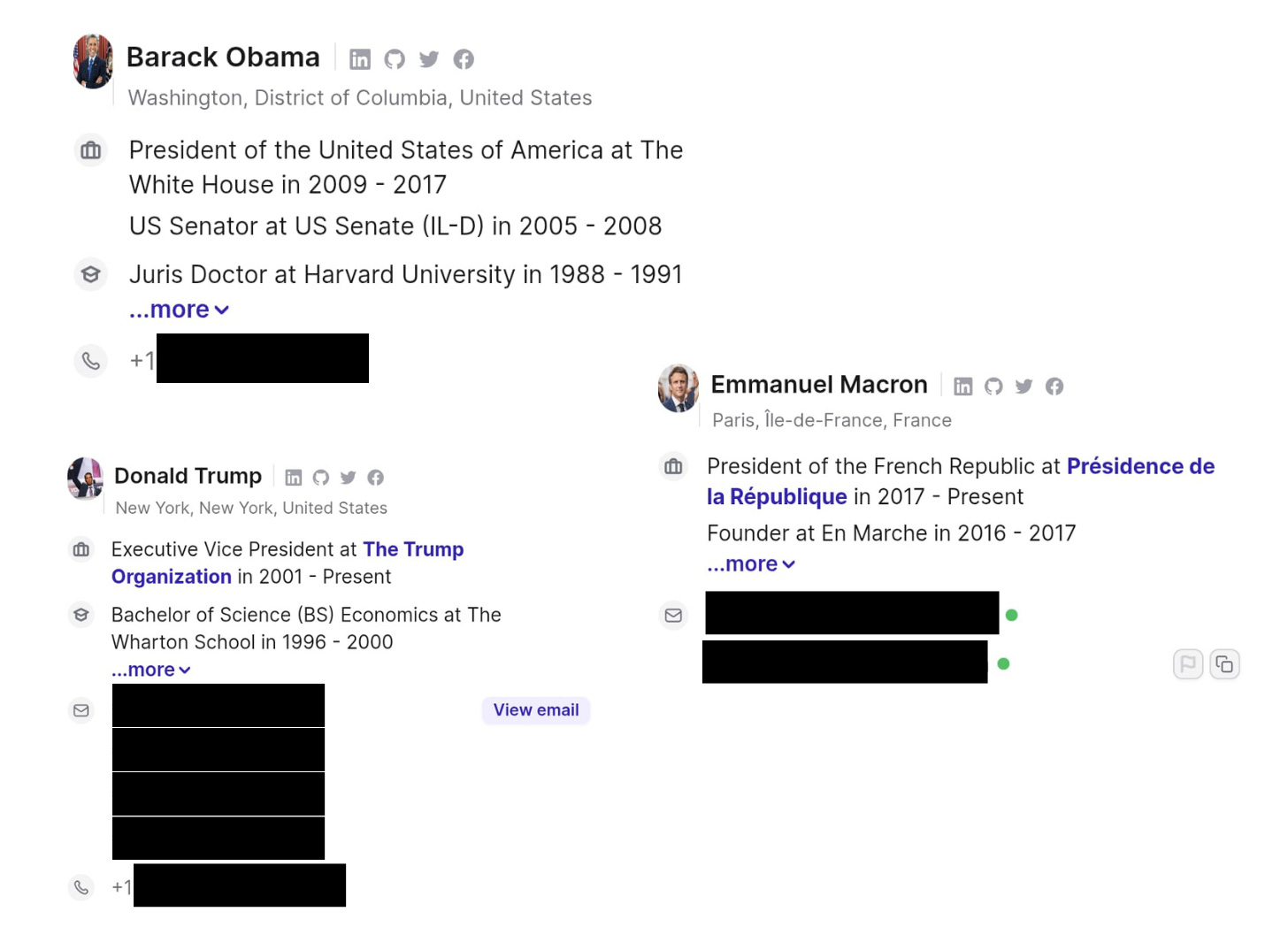

Barack Obama, Donald Trump Jr listed

A Deepcut search also found profiles with listed phone numbers belonging to former US President Barack Obama and Donald Trump Jr. Deepcut could not verify the accuracy of the phone numbers. A search for French President Emmanuel Macron disclosed only two email addresses.

The company, whose name Deepcut is withholding for ethical considerations, claims it sources its data by crawling the web for emails and phone numbers, using artificial intelligence to match contact information.

As reported by Ette Media, its Chrome extension suggests users can find emails and phone numbers on LinkedIn, but LinkedIn denied there had been a data breach, adding there was no proof phone numbers listed on the third-party website originated from them.

Little Australia can do about it

LinkedIn’s remarks to Ette Media regarding the lack of proof is the precise legal weak point that hinders accountable action, according to Lizzie O’Shea, an Australian human rights lawyer and founder of Digital Rights Watch.

“It is virtually impossible for an individual to stop the collation and publication of information without clear provenance,” she told Deepcut.

As Australian privacy laws do not extend to foreign entities with no footprint in Australia, the legal focus would need to shift towards the source of the leak – i.e. where the US-based company obtained this data. But even then, Sulston says “it would be incredibly difficult to prove this outside of the originating company self-reporting a data breach”.

Repeated breaches exposing millions

That personal data is being harvested from all corners of the web, packaged and sold for profit is the potential result of repeated data-exposing cyber attacks.

Several notable cyber attacks in Australia in recent years have exposed millions to data breaches, including:

2022 - Optus - exposing the personal data of 9.8 million people

2022 - Medibank Private - 9.7 million people

2023 - Latitude Financial - 14 million people

2025 - MediSecure - 12.9 million people

2025 - Qantas - 5.7 million people

And these are only the major breaches. According to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, there were 1,113 notifications of data breaches in 2024, with health service providers and the government the top two targets for malicious or criminal attacks.

“In terms of preventing personally-identifiable information leaking onto the internet, once it’s out there it’s virtually impossible to delete. The internet is fundamentally a data-copying machine and legislation can’t change this,” Sulston says.

What the government can do

“There are options available to governments to take action to stop this kind of behaviour,” O’Shea says. “For example, we could impose greater restrictions on the transfer of personal information outside of Australia, or mandate that such transfer come with an undertaking to comply with Australian laws.”

O’Shea also suggests Australia could follow in California’s footsteps and grant Australians the “right to delete” their personal data online.

“We also need to fix gaps in our privacy laws, including exemptions for political parties and small businesses that are not justifiable in the modern digital age,” she says.

“It’s common for Australians to be reliant on US tech companies for services, but that doesn’t limit lawmakers from regulating use of our personal information. Indeed, if anything, it makes it more important,” she says.

At a society level, Sulston adds, people should reduce the amount of personally-identifiable information they put on the internet.

This also requires the government to get stricter on companies requesting unnecessary personal details.

“Does LinkedIn really need my phone number?” he says.

“We need to focus on anonymity and pseudonymity as fundamental tools to protect our privacy online.”

Comment has been sought from the minister of communications, Anika Wells, and the eSafety Commissioner.